The Catholic church has

increasingly been accused of attempting to conceal

repeated incidents of priests sexually molesting

children. While more and more people are accepting the

likelihood that the church has been harboring

pedophiles, few people are willing to believe that the

sexual molestation of children is a fundamental part of

church doctrine. In his new book,

Original Sin:

Ritual Child Rape & The Church, Dr. DCA

Hillman strikes at the foundation of Christianity,

providing evidence that early priests ritually sodomized

young boys during their catechism. Hillman argues that

this practice was part of a cultural war early

Christians waged against

a

Roman society that praised sex and nubile girls.

He claims that early priests sodomized these boys in

order to "save" them from serving in oracle cults, as

these popular pagan religions required that the children

who participated in their ceremonies be

sexually

inexperienced. I caught up with Hillman to

question some of his radical ideas.

On page 26, you write, "The mystery of the

catechumen's initiation was a ritualistic form of

sodomy, designed by the church to turn young

believers away from the ills of sexual desire." What

is the most condemning piece of historical evidence

proving that early Christian exorcists ritually

raped boys during their catechism?

The most nauseating smoking guns of the child rape

ritual are the actual written works of the

Catechetical schools that the Christians, in

hindsight, probably should not have preserved. Read

through the treatises of Cyril of Jerusalem;

when you end up in his basement with a room full of

naked kids being blindfolded, oiled, fondled and then

bent over by some priests and their bishop who

ardently apply the "fires of temptation," you will

experience a bit of the horror firsthand. The

Christian author Prudentius fills in the gaps by

telling us the "fires of temptation" are acts of anal

sex — the most dreaded enemy of the Christian pilgrim.

It will also make you ill to read Cyril's

post-initiation counseling advice, where he instructs

his priests to make sure these young men — after they

are bathed, or baptized — are told that submitting to

a sexual encounter does not mean you have sinned if

you didn't actually enjoy it; from a textual

standpoint, it appears that the majority of them

didn't.

On page 94, you write, "The war on sexuality

under the Christian hierarchy was not a war on

masculine sexuality; it was a war on everything

feminine." In the book you repeatedly make the point

that Christians saw attractive young women like Eve as

the ultimate evil, as they could tempt young men to

contaminate themselves with sex. You also point out

how the Greco-Roman world praised sex and women,

particularly beautiful, young female goddesses, or

korai. Did the early Christians not worship Jesus's

mother Mary to the degree modern Christians do? Also,

if women were held in such reverence in Roman society,

why were they not allowed to vote or hold public

office?

It is a historical half-truth — a fragment of the

Christian lens of modern academia — to say that women

were not allowed to vote or hold office in antiquity.

For example, ancient priestesses were highly visible

public authorities who presided over festivals and

holidays, directed public performances, and were given

titles that carried genuine civic, social and

political power. The oracles alone, in places like

Delphi and Dodona, granted permission for war

campaigns, endorsed the founding of colonies, presided

in cases of extreme judicial difficulty — like an

ancient supreme court — and even practiced medicine.

They also founded colleges where the first westerners

were educated — they called them Museums. Priestesses

initiated the overthrow of dictators, guided military

expansion, and created careers for unheard of people

like Socrates, a man who would have died in complete

obscurity if not for the public endorsement of a

certain female oracle. We believe women were oppressed

in antiquity because our society concentrates power in

the hands of voters and the officials they elect. We

have no equivalent of the ancient priesthoods, with

their extreme social and political influence, so we

often fail to grasp the profound impact of women in

the ancient world; we lack their perspective.

In modern times, the

condemnation of abortion and birth control by

Christian leaders makes sense as a political

strategy, as it leads Christians to procreate at

higher rates, potentially creating more followers.

In a society like Rome that celebrated sex, would

not the condemnation of sex and women be a huge

tactical error in terms of enticing new followers

and attempting to grow the religion?

As the pagans who lived during the rise of the early

Church said, the draw of Christianity was its fear and

exclusivity. Followers of Christianity, in its early

years, were not born, they were forged in the fires of

temptation. The idea of being bred into Christianity

is distinctly post-classical. Nineteen centuries ago,

Christians didn't enter the kingdom of heaven by

post-natal sprinkling or baptism; they earned the

right to sit next to the throne of God by rebuking the

Devil and banishing desire. Birth control had nothing

to do with Church recruitment in antiquity; it was all

about indoctrination and the rejection of the "flesh."

After all, (as the pagans pointed out) the Christians

were preparing for the imminent return of their

messiah and the wholesale slaughter of the Romans.

Breeding the next generation of believers took a back

seat to recruiting soldiers for Armageddon.

It's about consent. Laws and customs vary

significantly from city to city but you can get into

trouble in Greece and Rome for forced intercourse with

any age group; you can even be prosecuted for forced

sex with a slave. Children were especially protected;

as a matter of fact, Artemis and Apollo, two of the

most commonly celebrated gods of the ancient world,

who had temple complexes everywhere, were the

guardians of pre-pubertal children. If you assaulted a

kid, you not only brought down the wrath of ancient

civic judicial systems, but you could also be dealt

with by the religious authorities and their own laws.

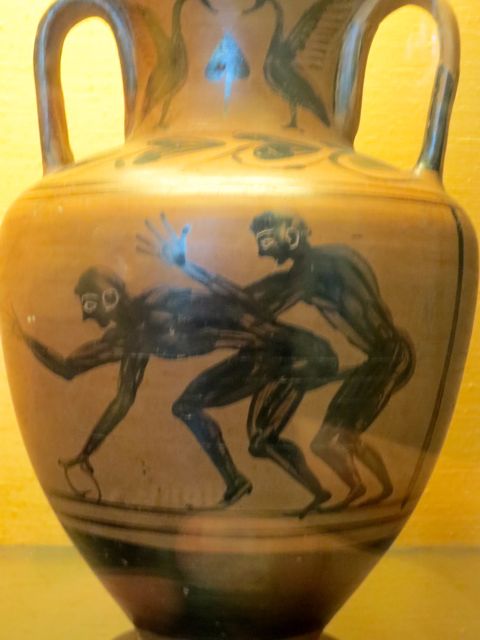

But again, the focus in the texts and the famous vase

paintings seems to be on consent and post-pubertal

goings-on. Ancient physicians even argued that teenage

girls who did not have intercourse within the first

few years of puberty ended up with psychological

damage — so their sexual ethic is based on a natural

model and therefore puberty and consent driven.

However, assault ("hubris" in Greek) is assault, and

what the Christian priests were forcing upon pubertal

and pre-pubertal converts bears no resemblance

whatsoever to what the Greeks and Romans did — and

that's why the Christians were so afraid of the pagans

finding out.

On page 103, you write, "Under [the priests']

direction, sexual abuse became a potent means of

cementing doctrine in the psyche of new members by

reinforcing their teachings with physical and mental

trauma." If these priests were willing to physically

and mentally brutalize these boys in attempt to save

their souls from being contaminated by sex and

women, why do you think these exorcists did not

simply castrate these boys to achieve the same end?

Ancient priests, bishops and specialized exorcists

attached to catechetical schools had to walk a very

fine legal line. They were still members of the pagan

societies in which they lived and the pagans had been

complaining for many decades that the Christians did

not respect their laws or their government. Pagans

publicly condemned Christians and their leaders for

their odd sexual behaviors and the priests — as we see

in Cyril of Jerusalem — were forced to keep many of

their activities on the down low; otherwise they could

be prosecuted, as they freely admit. Origen, a leader

of the Christian faith who was also associated with

the catechetical school in Alexandria, cut his own

dick off to avoid contaminating himself with a woman.

Why didn't the early Church castrate en masse?

Probably because the Romans had them under constant

scrutiny and would have brought charges against them —

as they did numerous times.

It's all about beating the competition. When

Christianity was young, it was competing with some

very heavy religious hitters. Romans, Greeks,

Egyptians, Etruscans, Phoenicians, and many Middle

Eastern cultures — including the Arabs — worshiped the

ancient power couple known by the Greeks as Aphrodite

and Dionysus. Pan and his rowdy satyrs — who promoted

the use of a crazy, designer sex-drug concoction that

contained opium, cannabis and hallucinogenic

nightshade plants — were the popular guardian figures

and functionaries of these universal cults; they

promoted the veneration of the Queen of Heaven, or

Aphrodite-Urania, the source of sexual desire in the

world — Mother Nature, if you will. The symbols of

their devotion were the huge erections

they dragged around and the dildos

that were actually used in their religious practices.

It made perfect sense to the Christian authorities who

steered Church doctrine that this horny, intoxicated

half-goat figure was the obvious equivalent of their

masculine woman tempting Devil. Pan and his satyrs

literally got demonized so that pagan cult members,

who competed with the Christians, could be absorbed by

this new religion. It's all about beating the

competition.

Considering how controversial this book is,

why did you not include a list of bibliographic

references at the end in order to point your

objectors directly to the first hand evidence in

their own doctrine? Was it just a matter of the cost

of printing?

I did better than that. At the request of my editors

I submitted footnotes with sources for my major

assertions and the direct quotes used in the body of

the text for the first manuscript. So why didn't the

notes make the final cut? Ronin Publishing is well

aware that footnotes, endnotes and references scare

people away from books, and they knew that the

findings of "Original Sin" were so important that they

should be made available to the public at large —

rather than the dozen or so academics who would have

bothered to purchase a heavily referenced dissertation

of the subject; if I had provided an analysis of all

my sources, the fact that the early Christians

ritually sodomized children would have been completely

ignored. Ronin Press wanted the findings to reach the

public; and I think they were right.

If humans are simply animals with oversized

brains existing without a god, and such concepts as

good and evil are only ideas, what does the repeated

occurrence of child rape throughout history reveal

about human nature?

I have no idea. Maybe some anthropology grad student

should figure that out. All I can tell you from the

texts I've studied is that child rape is an integral

aspect of Christianity. As I work on the sequel to

ORIGINAL SIN, it's looking more and more like ritual

rape was not even performed exclusively by pedophiles.

What? Is that possible? Yes it is; ancient Christian

priests actually believed their own theological

justification for sodomizing children, and don't

appear to have always acted out of prurience — they,

like their victims, were motivated by fear. Don't get

me wrong, some of them clearly enjoy talking about

naked boys in a way that betrays they are pedophiles,

but some seem to be just taken up by their faith. And

if fucking a kid into heaven works, then I suppose

they were just doing their jobs. What does that say

about human nature?